- Resilient Cyber

- Posts

- Cybersecurity's Delusion Problem

Cybersecurity's Delusion Problem

A discussion about cybersecurity's inability to accept that the world (business) doesn't revolve around them

Cybersecurity's Delusion Problem

A discussion about cybersecurity's inability to accept that the world (business) doesn't revolve around them

One challenge cybersecurity heavily struggles with is accepting that the world (and business) doesn’t revolve around them.

For all the FUD driven metrics around data breaches, security incidents, costs, vulnerability exploitation and more - the reality is that organizations often have more pressing critical risks than cybersecurity (a point I will help bring home as we close the article).

Thanks for reading Resilient Cyber Newsletter! Subscribe for FREE to receive weekly updates with the latest news across AppSec, Leadership, AI, Supply Chain and more for Cybersecurity.

In our career field, we’re incredibly effective at focusing on cybersecurity risks.

Things such as:

Vulnerability exploitation

Compliance deviations

Threat Actors

Misconfigurations

And the list goes on, and on.

However, the reality is that cybersecurity is one business/mission risk, among many.

The organization is concerned with a much broader world of risks and considerations, such as:

Keeping pace with competitors

Market share

Revenue

Brand Awareness/Exposure

Customer Satisfaction

Mission/Business Outcomes

From efforts such as CISA’s Secure-by-Design to the latest U.S. National Cyber Strategy, we hear themes pushing for businesses/organizations to prioritize security on par with competing interests such as feature development and speed to market.

The problem of course is, that’s not how the real world works.

Consumers generally aren’t making purchasing decisions based on how “secure” something is (assuming we could even define what “secure” means and communicate it to the general public in a way they understand).

Purchasing behaviors are driven by features, capabilities, functionality - by what adds value to their life, makes things easier, is convenient, and yes, by what is affordable (higher levels of security and rigor has a cost, even if we want to pretend it doesn’t).

Interested in sponsoring an issue of Resilient Cyber?

This includes reaching over 6,000 subscribers, ranging from Developers, Engineers, Architects, CISO’s/Security Leaders and Business Executives

Reach out below!

Misaligned Incentives

As discussed above, we keep demanding organizations, and more locally, developers prioritize cybersecurity on par with feature development, speed to market and other objectives.

The problem of course is the business isn’t incentivized to do that, because it would be financially irresponsible to do so. The goal of the business is to maximize shareholder value.

The overwhelming majority of customers and consumers want feature rich, capable products and they want them fast.

If security was a wide-scale competitive differentiator we would have long ago seen a shift in purchasing patterns from technology vendors with highly visible and impactful security incidents to those without them, but we haven’t.

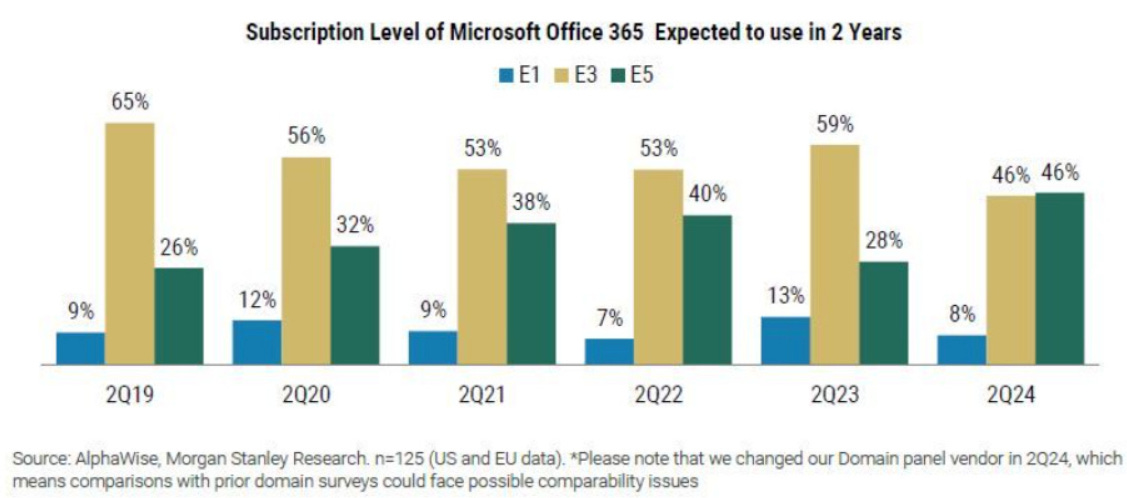

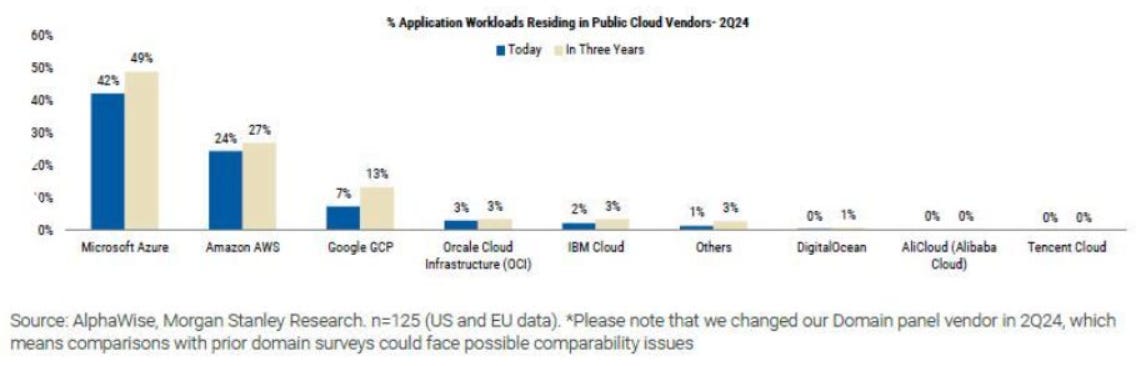

Microsoft is an excellent example, whom despite having several highly visible and critical security missteps continues to see growth in consumption, market share and revenue, as evidenced below.

Not only is there potential cost implications for products that invest in additional security and rigor, there would be additional considerations for the business, such as the switching costs involved of changing products, platforms and vendors, and not just financial costs, but expertise among the staff to consume and effectively use whatever new products were introduced.

Bringing the point more personal, Developers aren’t professionally incentivized to prioritize security (which can be interpreted broadly) over things such as feature and code velocity, burning down product backlogs, and overall productivity - because that isn’t how they are measured within organizations and it generally wouldn’t lead to career advancement, increased compensation and upward mobility.

In fact, in part due to the cultural norms and behaviors in security, many developers actually describe security as a “soul withering chore”.

For another example, OWASP recently had to cancel their “Dev Day” event due to, wait for it, “a lack of interest”.

This speaks to various points, as made by Security Champion Dustin Lehr, such as:

The poor relationship between security professionals and developers

A general lack of awareness and interest in Security from Developers and their leadership

The problem isn’t just specific to Developers either, as it traces to the highest level of organizations.

A recent report by ExtraHop in an article titled “C-Suite Involvement in Cyber is Little More Than Lip Service” highlighted some concerning takeaways.

They included the fact that 4/10 of organizations look to their executive leadership to help assess and weigh in on cyber risks but only 1/5 of organizations actually feel there is a high-level of commitment and involvement from the C-Suite and board when it comes to security. 88% of organizations were cited as lacking direction and attention from the C-Suite and Board when it came to cyber.

This is despite pushes from SEC and others to make cyber a boardroom priority.

The article points out the quiet part out loud, that we’re seeing a lot of virtue signaling when it comes to C-Suite, Boards and organizations caring about security but little real actual investment and involvement.

This isn’t surprising, as they are largely more focused on factors that directly drive revenue, market share, ROI and of most concern to shareholders.

Unidirectional View of Risk

In cybersecurity we also have a unidirectional view of risks.

Risks in our opinion are always bad.

We inventory, catalog, curate and idolize them in a myriad of systems, documents, dashboards and more.

In reality though, it is the risk takers who tend to reap the rewards.

The organizations that make bold bets, cast a vision, pursue it and invest the resources to outpace competitors often are the winners.

Those who played it safe, lived in fear, failed to act and were reactive end up as laggards, disrupted by new entrants and innovators.

Sure, there is a risk of PII exposure, a security incident, vulnerability exploitation and more.

But guess what, there is also significant risks when it comes to failing to keep up with competitors, being late to the market, not being cost competitive, failing to satisfy users/customers and most importantly, not taking risks.

We see this in industries such as the Federal/Department of Defense, where military service members have to write open memos begging for the bureaucracy to “fix their computers” and an entire ecosystem of silicon valley/tech innovators and Federal/Defense leaders pleading for acquisition and cyber overhaul as they struggle to provide effective digital services to citizens or increasingly fear peer nation states like China are going to eat their lunch and leave the U.S. ill-equipped for future conflicts which will largely be digital, with cyber as a domain of warfare.

In cyber we often forget that we’re not in the business of eliminating risk, we’re in the business of managing it.

Opportunities exist on the other side of risks.

Insufficient Consequences

Another uncomfortable truth for us is that there simply are insufficient consequences for neglecting security.

As pointed out by CISA, Jen Easterly, the U.S. National Cyber Strategy (NCS) and others, it is far more economically efficient to externalize risks onto downstream customers, consumers and society than it is to bear the cost of rigorous cybersecurity.

In the latest IBM Cost of a Data Breach Report (which is hotly contested by those with deep statistical expertise), the average cost of a data breach is $4.88M. Implementing effective cybersecurity in long complex enterprises has significant costs. From tools, licensing, staff, managed service providers and more.

In fact, despite “heavy” investments in security tools and products, organizations continue to experience breaches. It was stated that despite having 53 or more security solutions, 51% of organizations experienced a data breach over the last 24 months.

Many organizations simply make the risk calculus that it may be cheaper to pay any regulatory or legal/customer consequences than it is to implement a sufficiently effective security program consisting of people, process and technology.

That is from the organizational perspective.

On the vendor side of the equation, most software suppliers are heavily insulated from any significant liability. Software is generally sold “as-is” with little promise of recourse in the face of incident or exploitation, at least generally not up to the level of the financial consequences of data breaches and incidents. We saw this play out recently with Crowdstrike as an excellent example.

While there is of course a lot of discussion around concepts such as software liability and safe harbor, including from the U.S. Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD) and others, the truth is there is still much to be worked out on that front, such as what measures “secure”, if it would be a self-attestation or third-party assessment model, and inversely, what safe harbor and sufficient due-diligence would look like.

Much of these are captured in papers, such as Jim Dempsey’s “Standards for Software Liability: Focus on the Product for Liability, Focus on the Process for Safe Harbor”.

Echo Chambers

For all the discussion of Secure-by-Design, Software Liability, and the need to prioritize security with competing interests such as speed to market, feature velocity and revenue, much of it is occurring in an echo chamber of security practitioners and security product vendors.

Some examples of this include the fact that much of the discussion about Secure-by-Design or Security in general of course happen at cybersecurity events and conferences such as RSA and Black Hat and not the broader business ecosystem.

Additionally, taking a look at an effort like the recent CISA “Secure-by-Design” pledge you can see a large portion of the signatories are security companies, or companies to make revenue from cybersecurity. Examples include:

Apiiro

Armis

AttackIQ

Axonius

BlackKite

CodeSecure

Dragos

Fortinet

Huntress

TrendMicro

The list goes on, but you get my point.

While we’re hoping, wanting and wishing for secure software and products, the business is off doing what businesses do - focusing on generating revenue, profits and returns for shareholders.

The Need for Change

We continue to hear mantras in cyber such as “security must speak the language of the business”

Yet, most of our discourse still heavily involves terms like vulnerabilities, CVE’s, threats, exploitation, and a litany of security tool acronyms that keeps growing (e.g. SAST/DAST, CSPM/SSPM, SCA, ZT, CIEM et. al) and very little use of terms the business focuses on such as revenue, profit, customer acquisition/CAC, ARR/NRR and more.

This reality is even being felt in the job market, as factors such as high interest rates, growth corrections coming out of the pandemic period, and more have led to widespread layoffs in cybersecurity.

I think Cybersecurity Headhunter James Warren really nailed it in a recent LinkedIn post on the topic of layoffs and the state of the job market.

“I think one of the biggest things that CISOs will take away from the difficult market though in the last couple of years is that companies are very prepared to sell security risk – by not investing in security programs – to offset what they perceive as more important risks in other areas of the business.

A security leader’s ability to calculate and communicate the importance of security risk, particularly in the context of your company's business risk as a whole, will be your first and last line of defense in future economic downturns.”

Emphasized above is the point that organizations are making investment decisions to address risks in other areas of the business beyond cyber, simply because as discussed throughout this article, they are often more impactful and consequential if not mitigated or remediated.

If we want to fix this, we need to realize the world and the organizations and missions we serve don’t revolve around cybersecurity, as much as we wish it did.

The sooner we realize this, act accordingly and focusing on business value and outcomes, the sooner we will be positioned to function as an actual business enabler and asset to the organization operating in a digital paradigm and breakdown historical cultural silos we’ve driven due to our behaviors in security.