- Resilient Cyber

- Posts

- Cybersecurity Workforce Woes

Cybersecurity Workforce Woes

A look at the current cybersecurity workforce challenges and the factors involved

Welcome

One of the most discussed topics in the industry right now is the cybersecurity workforce. It is a topic that draws heated discussion, strong opinions and often contradictory data and perspectives.

On one hand we hear that there are hundreds of thousands of vacant cybersecurity roles every year and that every organization is struggling to attract and retain cyber talent.

On the other, we have an endless feed of cyber professionals with years of experience, degrees, certifications and more all struggling to find roles and sharing their experiences on platforms such as Reddit, LinkedIn and others.

In this article we will attempt to unpack aspect of the cybersecurity workforce woes we continue to hear about.

Thanks for reading Resilient Cyber Newsletter! Subscribe for FREE and join 7,000+ readers to receive weekly updates with the latest news across AppSec, Leadership, AI, Supply Chain and more for Cybersecurity.

Interested in sponsoring an issue of Resilient Cyber?

This includes reaching over 6,000 subscribers, ranging from Developers, Engineers, Architects, CISO’s/Security Leaders and Business Executives

Reach out below!

Open Roles

First off is the topic of open roles, which is often the origin of discussion when we hear about “cybersecurity workforce challenges”.

The most often cited source for figures thrown around is the ISC2 Cybersecurity Workforce Study, which is conducted annually.

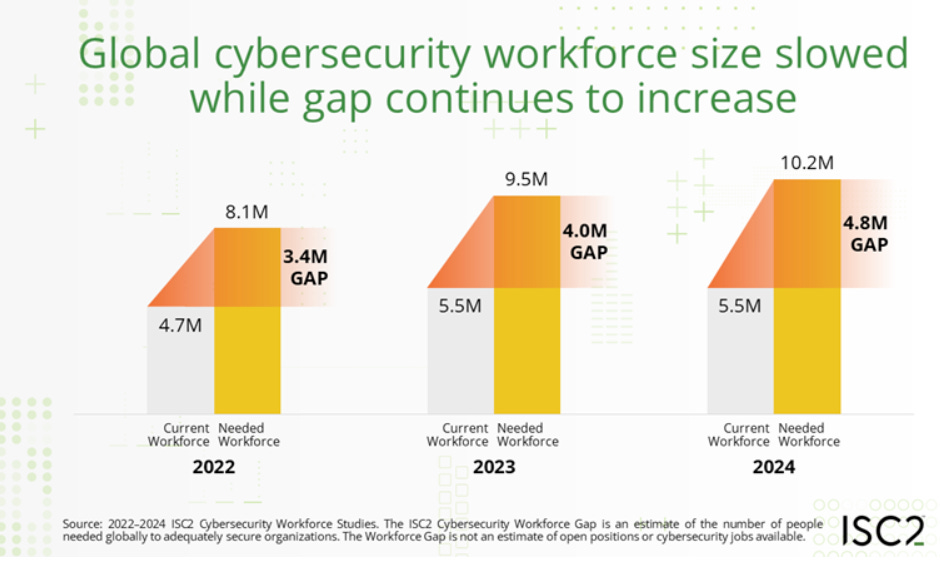

Per the 2024 study, key figures include:

An active cyber workforce of 5.5 million

A workforce “gap” of 4.8 million (which they say is up 19% YoY from 2023)

A total workforce of 10.2 million to satisfy the global demand (which they say is also up 8.1% YoY from 2023)

These figures seem to be initially supported by other reports, studies and articles, such as:

And many many others.

In fact, The White House Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD) has launched an effort dubbed “Service to America: Cyber is Serving Your Country” which is part of the broader National Cyber Workforce and Education Strategy.

The effort stresses the importance of having cyber talent to address threats to the nation and again, cited that hotly contested “500,000 - half a million!” open cyber jobs metric we continue to see.

Something worth noting is that the figures are often reported and repeated by organizations with a vested interest in the numbers being high. Examples include cybersecurity certification providers, who obviously make compelling providers for either existing security practitioners or those striving to break into the field looking to bolster their resumes with specific credentials that appeal to employers. This isn’t to say that cybersecurity certification organizations are bad, I hold many certifications from these very same organizations - but, we do need to be cognizant of incentives at play.

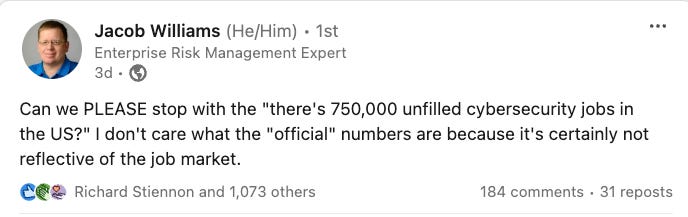

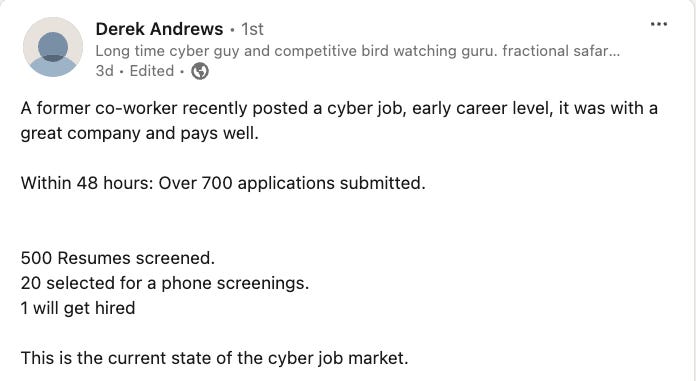

These figures are highly controversial with many industry leaders and practitioners taking aim at the metrics. A recent post from Jacob Williams that went viral on LinkedIn is a great example, with the comments being flooded with people calling the figures a lie, based on funny math, based on how organizations should optimally be staffed, and anecdotal examples of many practitioners struggling to find roles despite the supposed vacancies…

Another example below cites an early career level role and within 48 hours it received 700 applications.. as they say, “this is the state of the cyber job market”.

One interesting thought is, if cyber roles are seeing this level of applicants now, how do we think that will change when we removed requirements such as college degrees (which I agree with by the way) - they will see more applicants of course.

Some have even written articles (The big lie of millions of information security jobs) questioning the validity of the cited figures, instead citing vacancies on sites like LinkedIn as well as information from sources such as the Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS), which show much, much lower figures.

The article also points out efforts such as the ISC2 Workforce Study uses survey data, which isn’t perfect and nearly half of survey respondents are non-managerial mid and junior personnel both who don’t have a pulse on the state of hiring, nor even have hiring authority themselves.

On one hand we have hundreds of thousands of reportedly vacant security roles, and on the other we have many practitioners struggling to find roles, even when they have experience, education and credentials that in theory should make them appealing for employers.

So what gives?

Budgets

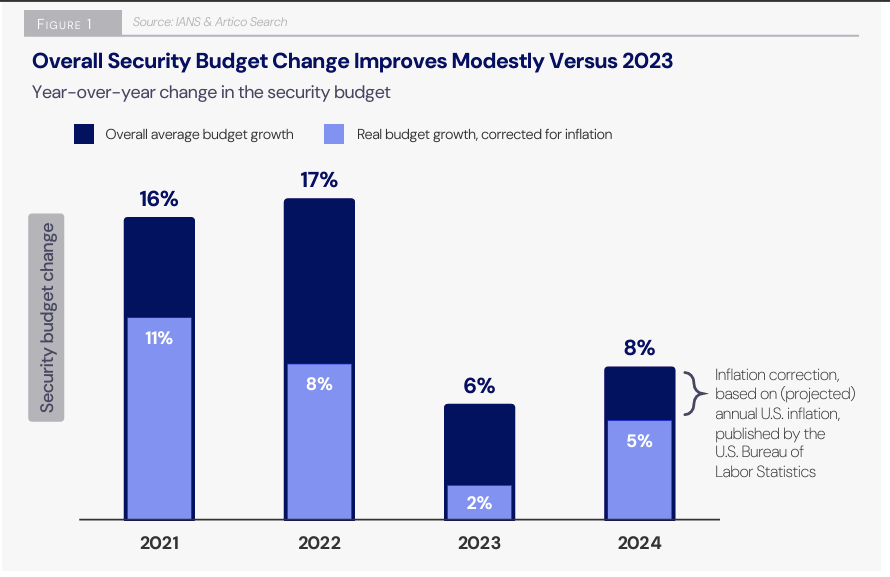

I previously mentioned the IANS Security Budget Report so we will use that to help orient the discussion. In the context of budgets overall security has often proved to be a bit more resilient to headwinds than broader IT.

That said, it isn’t infallible either. The IANS Security Budget Survey shows that security budget growth is 8% for 2024. While that is up from 6% in 2023, it is significantly lower than 16% in 2021 and 17% in 2022. Those periods of course saw hyper-growth due to factors such as lower interest rates, and explosive remote work trends.

Drilling down further into budgets, not all budget is of course allocated to staffing and personnel, and the IANS survey found that more than 1/3rd of CISO’s are maintaining consistent headcount for 2024, meaning teams aren’t expanding or hiring new staff, unless they are replacing someone who is departing.

The report even pointed out that “Security Budget Hypergrowth Has Ended”

This is impacting now just headcount but also purchases of additional tools and products, as CISO’s and security leaders have begun to rationalize their tool portfolios, justify additional spending, and demonstrate ROI of existing teams/tools.

Additionally, we’re seeing a push for “platformization” in the industry as organizations grapple with tool sprawl and leading security vendors advocate for leaning into robust security platforms as opposed to independent best-of-breed bespoke tooling.

New Entrants/Career Transitioning

One aspect of the cybersecurity workforce discussion is the supply side. These are either new entrants to the career field (e.g. recent graduates or folks making a career transition), the other is existing cybersecurity professionals actively seeking new roles, or at least being open to them.

We’ve seen a robust system begin to grow in academia, such as dedicated Cybersecurity B.S., M.S. and Doctoral programs. I actually have been an Adjunct Professor for University of Maryland Global Campus (UMGC) for roughly 7 years.

We’ve also seen the growth of the National Centers of Academic Excellent in Cybersecurity (NCAE-C) program led by the NSA and other Government entities. Schools can receive the NCAE-C designation which helps bolster their appeal to aspiring cyber professionals or those looking to further their education for career advancement.

The appeal of cybersecurity is being driven by bother higher than average salaries as well as positive employment trends with vacancies and shortages often being advertised, which drives people to pursue the field and seek out education, experience, and credentials to help them either break into the field or climb past their current role.

While cyber may have higher than average salaries, we’ve also begun to see some cooling down of cybersecurity compensation, especially with the growth of practitioners seeking new roles, shifting the dynamic from an employee market to an employer market. This is simple supply and demand economics playing out.

We’ve even seen various Government entities dedicate funding to cybersecurity education and research, such as the U.S. Department of Energy providing $15 million to universities with programs and curriculum associated with electric power cybersecurity, demonstrating the importance of cybersecurity to critical infrastructure.

We’ve also had incredible growth of asynchronous learning and education for cybersecurity (and broader IT/Software) with notable examples such as Udemy, PluralSight, KodeKloud, TCM Security and many more - all of which are available for cheap, with web-based and mobile applications to access courses and content.

These options coupled with formal education allow for folks to go learn, develop and build competencies that will make them compelling as they look to enter the cyber career field or aspire for new roles.

The challenge here of course is that pursuing formal education, asynchronous learning, digital courses and more do not automatically guarantee you will find a role or get the role you’re seeking.

I’ve known many folks who have graduated from degree programs, taking boot camps, certifications, labs, virtual based training and more only to still struggle to find a role.

Many factors play into this, such as the reality that organizations are often seeking those with experience, versus just education and credentials, to demonstrate that they are making a hire that will be effective in the role.

This of course presents a chicken and egg scenario, where many are struggling to break into the field due to a lack of experience, but can’t obtain the experience without someone allowing them into the field and get a chance.

Requirements

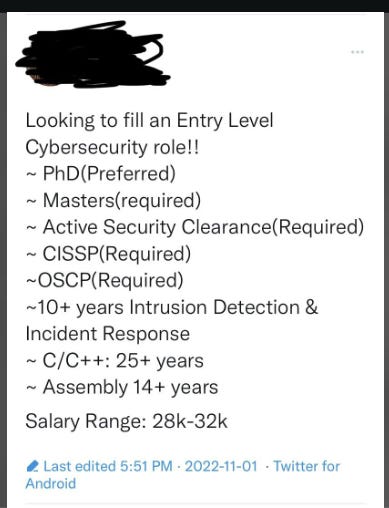

While the above picture from Reddit for an “Entry Level Cybersecurity Role” may be a joke, it isn’t too far from the reality of what we all too often see in cybersecurity.

It isn’t uncommon to see entry level roles with ridiculous requirements in terms of education, experience, credentials and expertise. The same happens are various levels of security roles.

It is driven by a variety of factors, such as talent/hiring folks being out of touch with the career field they’re hiring for, writing poor JD/PD’s and hiring requirements, often requiring a combination of experience, education and credentials that simply do NOT exist.

Couple that with teams and organizations trying to get by with less due to funding and budget constraints, seeking to maximize the skills of several individuals into a single role to capitalize on whatever budget they do have.

This requirement squeeze doesn’t just stop at the door, it often perpetuates post-hiring, as cybersecurity professionals face widely reported systemic challenges with stress, fatigue and burnout.

This is due to factors such as the ever constant potential for threats, incidents and impact, longstanding culture fractures with peers such as Developers and Engineers (which are often self-inflicted due to how we operate and engage) as well as the broader business.

Teams are often asked to juggle a carousel of security tools that simply isn’t sustainable, leading to organizations having a slew of security tools that aren’t fully deployed, implemented, configured, tuned, optimized and preventing organizational risks (often actually serving as an increased attack surface themselves).

Harsh Realities

While some of the items we have discussed above are broader economic, social, and systemic aspects of the cybersecurity industry, there are also some trends at play that are problematic, and truth be told, are hard for some to accept as well.

CISO’s

The perceived pinnacle of the security career field is the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO). Some have begun to explore other roles post-CISO or as an alternative to CISO, such as moving into CTO roles, venture capital, advisory/board roles and more, but that is a topic for another article.

The CISO generally oversees the broader security team, tool portfolio, and resources (both human and financial capital and how it is allocated). This is great, but does have the potential for some undesired behaviors among a subset of the CISO community.

Common patterns and pain points include:

Average CISO tenure ranges from 18 months on the short end to 4 years on the longer end. This often means short stints especially when you account for getting their footing, lay of the land, and implementing their vision, which often includes pursue new initiatives, purchases and projects. This leads to churn among the subordinate staff and a jerky experience when it comes to products and tooling.

Rises in CISO job dissatisfaction and liability concerns often put CISO’s in a position to be risk adverse, leading to friction among the business who is often seeking to use technologies, tools and products in new ways, as well as when it comes to hiring junior and green talent, who could potentially introduce risks which the CISO ultimately would have to answer for.

Questionable ethics, behavior and relationships among CISO’s has begun to come under scrutiny lately (now called the “Gili Ra’anan Model”), as CISO’s are primarily targeted by security startups looking to pitch their solutions and products to organizations for consumption and purchase. This includes lavish dinners, events, advisory roles and even equity in companies or venture capital funds. If these startups go on to succeed through M&A or IPO’s it of course means financial benefits for the CISO’s who helped the products grow in the market. Couple this with short tenures for CISO’s, who often go on to work for product companies, it is clear that there are much stronger incentives for CISO’s to expend resources on products and tools than there are on staffing. This sort of behavior is similar to what we often call “Resume Driven Development” where individuals pursue big visible projects to help bolster their resume for future roles and opportunities, even if the efforts aren’t in the best interest or required by the organization they’re implementing them for.

VC/Products & Tool Centric Approaches

Another major factor that ties to some of the topics discussed above involves Venture Capital, Startups/Product Vendors and a pervasive tool-centric approach in cybersecurity.

It is widely reported that cybersecurity tool sprawl is out of control (and getting worse). Estimates for organizations are as high as 130 in some cases and between 70-90 in others. In either scenario, organizations are juggling tens, or hundreds of security tools to combat organizational risks and scenarios.

This is grounded in a fundamental misunderstanding of cybersecurity.

Cybersecurity is something you do, not something you buy.

This isn’t to say we don’t need products and tools to mitigate organizational risks, but they aren’t now, and never will be a replacement for security practitioners.

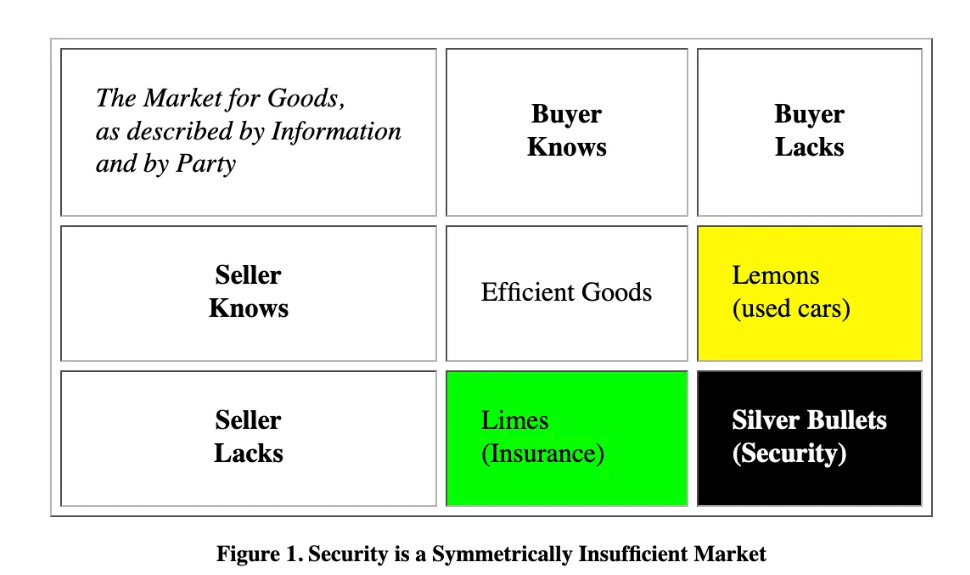

That said, cybersecurity is a market for silver bullets, as documented by Mayank Dhiman and Ross Haleliuk in the article. This means both the seller (product vendor) and buyer (customers) lack a solid way to truly understand and prove the effectiveness of products.

The security tool problem is also well articulated in Frank Wang’s article “Security Has Too Many Tools”, where he discusses how security uses tools as a shield to account for the fact that organizations don’t threat model or integrate security properly into their activities and try and bolt on endless options of security tools to save them from the problems of not properly integrating and conducting security-focused activities.

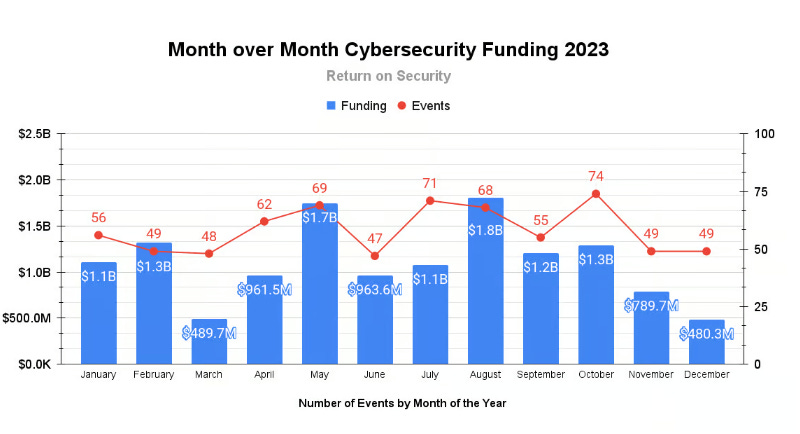

Another factor at play is the massive amount of venture capital at play in the cybersecurity market. For some figures from 2023, Return on Security provided a “2023 Cybersecurity Market Review” which showed the year had:

684 funding rounds across 100+ unique product categories worth ~$12.7B

259 M&A transactions across 70+ unique product categories worth ~$40.5B

This means billions of dollars flowing throughout the cybersecurity industry, seeking ROI. This contributes to situations such as cybersecurity events which are absolutely dominated by product vendors, pitches, marketing, buzz and deal making - little to none of which focuses on the workforce, but instead, on products.

Walk the halls of Black Hat, RSA, Gartner, and any other notable industry events and the ratio of dialogue focused on products compared to the workforce is palpable.

That’s because products drive revenue, unlike discussions related to the cybersecurity workforce.

The irony of course is that most organizations would be better off with less security tools and more competent security practitioners help implement robust security programs, with a combination of the triad of people, process and technology, the last piece deserving the least emphasis, since security is something you do, not that you buy.

Security is a process, not a product.

That process is carried out by people.

Yes, they do and always will need tools and this isn’t to say that products aren’t needed.

In fact, with the explosive growth of vulnerabilities and ever-present challenges security has keeping up with both the business and the threat landscape, along with the advancement of AI, tools will continue to play an outsized role.

All that said, without a competent workforce, all security programs will fall flat.

Complacency Kills

One of the more uncomfortable aspects of the cybersecurity workforce discussion is that a subset of the cybersecurity workforce has atrophied. Much like a muscle, that when not used, we have some cybersecurity practitioners who haven’t kept up with broader industry trends.

While the industry experienced several transformative movements such as Agile, DevOps, Cloud, Zero Trust and now AI, some security practitioners have failed to keep pace, not making ongoing efforts to learn these new technologies, methodologies and innovations.

Due to longstanding struggles of organizations to attract and retain cyber talent, some have been able to hide out within their organizations in comfortable roles, with leaders and organizations reluctant to lose institutional knowledge and expertise.

This leaves those practitioners both with increasing limited utility as their organizations adopt the technological waves, as well as ill positioned to seek out new roles whether for career advancement, salary increases or due to layoffs as their employers hit economic headwinds or seek out talent with the necessary knowledge and skills for the digital modernizations they’re pursuing.

These practitioners tend to represent the stereotypical “office of no” and shut down innovation efforts within their organizations hiding behind FUD and compliance spreadsheets and other means to hide the fact they simply don’t understand the technologies or modern methodologies their development and engineering peers are seeking to utilize.

Ironically enough, their behaviors bolster organizational silos, which DevSecOps was meant to break down, and they also foster Shadow usage, which I laid out in my article “Bringing Security out of the Shadows”.

The cybersecurity workforce of the future will look much different than the one of the past.

It will:

Truly embody being an enabler, rather than a business blocker, and do so because they understand this actually makes the organization MORE, not LESS secure

Have technical depth, including being proficient with Code/Software, as everything increasingly moves to an as-Code Movement (including GRC with efforts such as OSCAL) (For a good read on this see “The Rise of Security Engineering” and “Security Needs More Engineers”)

Being business savvy, understanding that cybersecurity isn’t the only risk the business faces, nor the reason the business exists, which I laid out in my article “Cybersecurity’s Delusion Problem”

The cyber workforce of the future

It’s evident we have a complicated cybersecurity workforce ecosystem with various competing interests, incentives, struggles and gaps. Organizations continue to discuss challenges of recruiting and retaining cyber talent, and the figures seem to grow YoY (even if questionably).

The cybersecurity workforce of the future is likely to look much different, both in technical acumen, business/engineering collaboration and with the continued evolution of AI and its implications for automation, agentic-based workflows and more.

Conclusion

So while it is clear that there is widespread concern about longstanding challenges of recruiting and retaining security talent, there are also ongoing issues of experienced and qualified security practitioners struggling to find work among a sea of supposedly vacant roles.

Couple that with challenges such as a broken hiring and requirements system, a tool-centric industry being driven by venture, investment, competing interests for security leaders and it is a challenging environment.

The problem is further exacerbated by some stagnating efforts among a subset of the security workforce, broader economic headwinds and deep rooted behaviors that arguably create more organizational risk than they reduce.

While I cannot predict the future, I can give one piece of advice I am confident to stand behind. Want to stand out in the future of cybersecurity?

LEARN

And not just now, not in just your current role, not just with the technology of the day or current wave or hype but have a ruthless commitment to development and learning every day, all the time.

This field doesn’t slow down, and if you do - you will inevitably will get left behind.